The US department of health and human services (HHS) on Sunday confirmed the first human case of travel-associated New World screwworm in the country.

The case, investigated by the Maryland department of health and the US centers for disease control and prevention (CDC), involved a patient who returned from El Salvador and was confirmed on August 4. Maryland health officials said the patient has recovered, with no spread detected to people or animals, reported AP.

What are Screwworms?

New World screwworm is a parasitic fly that lays its eggs in open wounds or body openings. The insect is mainly found in South America and the Caribbean.

While rare in humans, the parasite poses a serious threat to livestock and has worried ranchers as infestations spread north through Central America and Mexico. US health officials said the CDC is working with the department of agriculture to prevent further spread.

Screwworms plagued the American cattle industry for decades, with Florida and Texas once considered hot spots, until eradication efforts in the 1960s and 1970s largely eliminated them in the US. The fly, a blue-green blowfly, gained notoriety in the 19th century after infestations were reported at the Devil’s Island penal colony off South America. Its Latin name roughly translates to “man eater," reported AP.

Female flies lay eggs in wounds or in the nose, eyes, or mouth of an animal or person. The hatched larvae feed on living flesh but do not spread from person to person. US health officials say the overall risk to the public is very low.

According to the CDC, people face higher risk if they travel to areas with livestock infestations, spend time near animals, sleep outdoors, or have untreated wounds. Symptoms include painful, slow-healing sores, foul-smelling discharge, or visible maggots around an open wound.

Symptoms and treatment

In humans, symptoms may include painful, unexplained wounds that do not heal, foul-smelling odors, or maggots visible in open sores. According to the CDC, people are at greater risk if they travel to areas with livestock infestations, sleep outdoors, or have untreated wounds.

Treatment requires surgical or manual removal of larvae, followed by wound disinfection. Health officials caution against trying to remove the maggots without medical assistance.

Are more cases likely?

Experts say it is possible. For decades, scientists controlled screwworms by releasing sterilized male flies, which mated with wild females to produce infertile eggs. However, lapses in this strategy, along with human and animal migration, have allowed the pest to spread north again.

New genetic techniques are being explored to suppress the fly population, and US officials are expanding efforts to prevent outbreaks.

Impact on US agriculture

The USDA has restricted livestock trade through southern ports of entry to limit the parasite’s spread. More than a million cattle normally arrive annually from Mexico, but imports remain restricted.

Currently, the only sterile fly production facility is in Panama City, producing 100 million sterile flies a week. Experts estimate 500 million are needed weekly to push the pest south to the Darien Gap, the rainforest dividing Panama and Colombia.

The confirmation of a US human case comes as cattle ranchers and beef producers remain on high alert. The USDA has warned that an outbreak in Texas, the country’s largest cattle-producing state, could cost $1.8 billion in livestock deaths, treatment, and labor.

Just over a week ago, agriculture secretary Brooke Rollins announced plans to build a sterile fly facility in Texas. Mexico is also constructing a $51 million plant in the south to support regional containment.

Indian Astronaut Joins ISS: Shukla's Mission Ushers in New Era for India's Space Program

Indian Astronaut Joins ISS: Shukla's Mission Ushers in New Era for India's Space Program

Ashada Gupt Navratri 2025: Unveiling Dates, Sacred Rituals & Hidden Significance

Ashada Gupt Navratri 2025: Unveiling Dates, Sacred Rituals & Hidden Significance

Rishabh Pant's Unconventional Batting Redefining Cricket, Says Greg Chappell

Rishabh Pant's Unconventional Batting Redefining Cricket, Says Greg Chappell

Moto G54 Price Slashed in India: Check Out the New, Lower Cost

Moto G54 Price Slashed in India: Check Out the New, Lower Cost

JPG to PDF: A Graphic Designer's Guide to File Conversion and Quality Preservation

JPG to PDF: A Graphic Designer's Guide to File Conversion and Quality Preservation

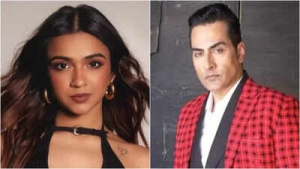

'The Traitors' Star Apoorva Mukhija Accuses Sudhanshu Pandey of Misogyny and Verbal Abuse After On-Screen Drama

'The Traitors' Star Apoorva Mukhija Accuses Sudhanshu Pandey of Misogyny and Verbal Abuse After On-Screen Drama

Van der Dussen to Captain South Africa in T20I Tri-Series Against New Zealand and Zimbabwe

Van der Dussen to Captain South Africa in T20I Tri-Series Against New Zealand and Zimbabwe

20 Minutes to a Healthier Brain and Heart: Neurologist's Simple Strategies to Combat Cholesterol, Blood Pressure, and Dementia Risk

20 Minutes to a Healthier Brain and Heart: Neurologist's Simple Strategies to Combat Cholesterol, Blood Pressure, and Dementia Risk

England's Audacious Batters Claim They Could Have Chased Down 450 in First Test Win Over India

England's Audacious Batters Claim They Could Have Chased Down 450 in First Test Win Over India

Popular Finance YouTuber "financewithsharan" Hacked: Security Measures to Protect Your Account

Popular Finance YouTuber "financewithsharan" Hacked: Security Measures to Protect Your Account